If you found this post via search, it probably makes sense to start with the first post in this series on the cost of shipping. The link to the full series is both above, and here.

What’s causing our current shipping disruptions and how much of a problem is it?

Starting in the early 2000s, container ship lines started building bigger and bigger ships.

The first ships that carried standardized intermodal containers carried 68 containers.

Now, the biggest carry more than 12,000 containers, or what they call 24,000 20 foot units.

And it was really in the early 2000s that these big ships started to come online, and they got bigger and bigger over time.

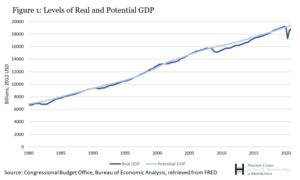

These were built on the assumption that international trade would continue to grow very quickly, as it had for decades.

What happened then was, in the financial crisis [of 2008], trade crashed.

After that, the growth of trade never recovered. International trade as a share of global GDP peaked back in 2008.

So there was a lot of excess capacity in shipping.

And every time a new ship came online with the capacity to carry thousands of containers, the excess capacity got worse.

To the point where you could send a container across the Pacific for less than $1,000 at one point.

When this happened, many ship lines went bust, or else found merger partners.

And so, what had been a very competitive industry, was transformed into what is basically an oligopoly today.

[NOTE: An oligopoly is where a market is dominated by very few sellers].

There are three groups of ship lines, and between them, they probably control 85 or so percent of the trade on the major trade routes.

And that means that they are able to control overcapacity.

There aren’t as many ships being built as were a few years ago because these three big groups keep a handle on this.

That means that when all of a sudden there is a spike in demand, as there was in the middle of 2020, that rates are going to go up.

That’s really what happened, after years and years of extremely low rates, rates started to rise in August or September of 2020.

Why did this happen? Aside from the demand?

In the early days of Covid, there were a lot of foul-ups, trade dropped off precipitously for a brief period, and then it picked up again, and at the same time, we had consumers in the wealthy countries who couldn’t spend on services.

So, in the midst of this crisis, people had a lot of money to spend.

They couldn’t go out to dinner, they couldn’t go on vacation, they couldn’t go to the theater.

They could buy things, and this actually increased the demand for physical products.

That’s a lot of what we’re seeing now in this sudden surge in exports from China.

How are maritime shipping prices determined?

The shipping business works almost entirely under contract, which is to say a big shipper, Walmart, Caterpillar, etc, will reach an agreement with either a ship line or with a freight forwarder, which will negotiate with the ship line on its behalf.

These agreements typically last six months, sometimes longer, and they’re typically filled with contingencies.

This means you can’t actually know what the cost of the shipment is.

A typical contract might say something like the shipper (the company with the goods to export) agrees to have at least 50 containers on the dock going from Shanghai to Los Angeles every Tuesday.

And any week in which it has less than 50 containers, the agreed price will be 20% higher.

And if over the entire six-month period it has fewer than so and so many containers, the price will be this much higher.

And if the shipping line misses a sailing, then it will have to pay a penalty of so much per container.

And those kinds of contingencies, and there are many of them, determine what the total price is.

So actually, a company can’t tell you what it will cost to send a container from Shanghai to Los Angeles on any given day.

It will only know at the end of the six months when it adds up all of the payments it’s made, and all of the penalty payments it’s received from the other party.

And then it becomes obvious in retrospect what the actual cost per container was.

So this is not public information.

Select “Next Post” below for the next post in the series.