With shortages and supply chain challenges in the news so much lately I tried to find a well done explanation I could share that didn’t fall into the trap of trying to explain something as complex as our global supply chains with overly simplistic answers, such as just run the port 24/7, just find more drivers, etc, etc.

Table of Contents

Supply chains are complex

In the past, I’ve worked for two logistics and supply chain companies (in an IT capacity), as well as one major global manufacturer (also in an IT capacity), and exposure to their business models and operations gave me an opportunity to see the complexity of managing supply chains.

When you consider that due to the nature of what supply chains are and how they work, the very nature of moving stuff around requires coordination and handoffs between companies, managing supply chains can get very complex very fast.

And very detailed

To give you a small glimpse into details of managing the flow of stuff, at one of the logistics companies I worked at we mapped out and timed the transit of EDI files within our systems, from receipt of the files from our customer to the importing of the contents of the EDI files into our transport tracking system.

At first, it took 6 minutes. We devoted a few weeks of effort to get that down to 2 minutes.

Why?

Because as a company we had a 2-hour response commitment to our customer and we felt it important to give as many minutes as possible to the operations people working to fulfill on behalf of the customer.

On occasion, they needed that 4 minutes, as we thought they might.

This overview video is excellent

This video gives an excellent overview of why there are so many shortages today, without falling into the “blame game” trap I’ve seen from so many these past few months.

Having said that, they do assign blame at the end, but it’s likely not what you’re thinking.

Video summary

The straw that broke the camel’s back

The Covid pandemic did not break our supply chains per se, but rather they exposed their fragility, and pushed them over the breaking point.

The straw that breaks the camel’s back is, after all, just a straw.

While technically Covid DID cause our current shortages, the vulnerabilities in our global economy made that possible and had it not been Covid it would have eventually been something else.

Structural vulnerabilities

In April of 2021, Boba Tea shops around the United States announced via Facebook and other mechanisms that they were having trouble getting the tapioca pearls, and other ingredients they use and that they either could not provide any of or had to provide less due to limited supply.

Some announced they had to raise their prices due to an increase in the cost of their ingredients.

There had been no dramatic increase in demand in the US, and in Taiwan, where the Boba Tea ingredients are made, they were producing their usual amounts.

The problem was at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach in California.

Two major US ports backed up

Ships were sitting at anchor, sometimes for weeks, waiting to unload.

A year prior a ship might have had to wait a day or two, the backlog had never before been dozens of ships for dozens of days.

Since transit time from Taiwan to Los Angeles takes about two weeks, adding ten more days was a near doubling of shipping times.

Why did the ports in Los Angeles and Long Beach get backed up?

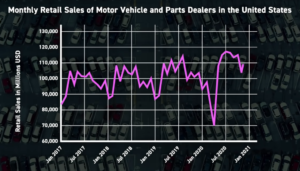

In late 2020, more Americans were going back to work, consumer spending was on the rise, and online shopping went through the roof.

With people staying home and saving money on movie theaters, restaurants, etc, people spent more of their discretionary income on stuff for their homes.

Much of which was physical stuff.

The volume of goods arriving from Asia increase drastically, and just under half of all imports from Asia come through the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

February of 2021 saw a 31% increase in ship traffic and a 49% increase in container traffic at these two ports over February of 2020.

At the same time, a large set of dock workers were off work either sick with Covid or quarantining due to positive Covid tests.

We ran short of shipping containers

We also experienced a regional shortage of shipping containers which is rippling through the global supply chain.

Due to shortages, the cost of a shipping container rose from $1,800 to $3,500 in one year.

In 2020 as much of the world entered lockdowns, China and its manufacturing industries were emerging from it.

The world bought masks, PPE, and regular stuff from Asia, they arrived by ship and got unloaded.

However, due to those countries being in lockdown, very little needed to be shipped back.

For every 100 containers that arrived in the US, only 40 left again.

So containers stacked up where they weren’t needed BECAUSE they weren’t needed, and they didn’t make it back to where they were needed, such as Asia.

And in the case of the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, due to their backup in getting ships unloaded, they couldn’t justify the time needed to load empty containers onto ships for transport back to Asia.

Which was made worse by a shortage of truck drivers

Additionally, due to truck driver shortages in the US, getting containers moved from their final destinations through the country back to the ports became a challenge.

Everything is connected to everything else

So, a shortage of shipping containers is making the shortage of shipping capacity worse, which is made worse also by a shortage of port capacity, which in turn makes the shortage of shipping containers worse, which itself is made worse by a shortage of truck drivers, all of which is causing a shortage of stuff.

Stuff like Boba Tea ingredients, and bicycles, and ketchup packets, and cars.

Scarcity

Americans, and people in other first-world countries, have become accustomed to relative abundance.

When you’re running out of something, it’s no big deal to just go get more. There’s plenty.

Lumber

Analysts predicted a decline in US lumber sales, but we experienced a boom in renovation and construction projects instead.

Lumber prices quadrupled.

Chlorine

Being stuck at home increased the demand for pool construction and the installation of hot tubs.

Which increased the demand for chlorine.

A fire at a chlorine plant in Louisiana led to shortages which in turn led to sky-high prices.

Ketchup packets

As dining switched from dine-in to take-out and delivery, demand for bulk ketchup fell while demand for ketchup packets increased.

Manufacturers did not spend to retool their factories to make more ketchup packets for what they saw as a temporary situation, so ketchup packets because scare and batches of them were literally being sold on eBay.

Tourists

Locations that rely heavily on tourists for their local economies have suffered greatly.

Rental cars

In spite of travel and tourism being down, rental cars are hard to find in many areas.

As the pandemic shutdowns got into full swing, rental car companies sold off much of their fleets as it was one of the few ways they could raise money to pay their bills.

Now that the US is getting vaccinated, demand for rental cars is growing, but supply is still very low.

And car rental companies aren’t able to replace their fleets because there is a massive worldwide shortage of new cars.

New cars

Again, as the pandemic shutdowns got into full swing, car manufacturers reduced their orders for parts and components as they expected the demand for new cars to fall.

And demand did go down, for a while. Then recovered much faster than expected.

Normally this is not a problem, as when demand grows, they order more parts and components and build new cards.

But, a critical component of all modern cars is computer chips.

Computer chips

The world is sold out of computer chips.

After the US-China trade war started, the chip manufacturers started stockpiling chips.

Then production shutdowns occurred at various plants due to Covid.

As people around the world stayed home, demand for consumer electronics went through the roof.

And now there is a competition for silicon between making computers chips and making vaccine vials.

Why are supply chains so fragile?

Ironically, because of the development of flexible manufacturing and just-in-time inventory management in the car industry. Specifically in Japan.

We are short of cars today because Toyota figured out how to be competitive with US car manufacturers.

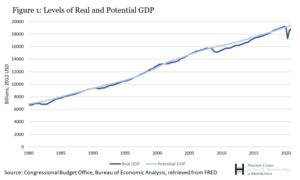

After WW2, American cars were much cheaper than Japanese cars because American manufacturers sold so many cars they had economies of scale that brought per unit prices down.

Because Japan had been bombed back into the stone age, they had to rebuild from scratch.

What we now call flexible manufacturing and just-in-time inventory management was at its inception known as The Toyota Production System.

It eliminated excess inventory which to the car manufacturer was shedding an expense they neither needed, wanted, nor could afford.

Just-in-time manufacturing is now everwhere

And I mean everywhere.

Retail as well as manufacturing

Ever been in the back of a large retail outlet? Supermarket?

There is very little storage space in the back. That the store is stocked is the result of regular frequent deliveries.

But, the world did just-in-time manufacturing not quite right

Physical distance matters

Japanese car manufacturers were able to operate efficiently with just-in-time inventory management because Japan was a fairly small set of islands, and the stuff needed for the next manufacturing step was, relatively speaking, not very far away.

It didn’t take long to move stuff from point A to point B.

This made their supply chains less vulnerable to disruptions.

Production leveling matters

Toyota calculated the average daily demand, and built to that, in spite of short-term changes in demand.

Excess inventory is not all inventory

By building to the calculated average daily demand, they kept some inventory, just not much.

But enough to keep their production flowing during short-term disruptions.

Cross functional teams

In the Toyota Production System, team members knew how to do each other’s jobs and this was considered to be critical to flexibility.

If it’s broke, stop the line

Allowing any worker to stop the production line when they saw something not working right created a culture of fixing things when the problems were small.

This helped create a culture of doing it right the first time.

But, what it lacked in resiliance, it made up in quarterly EPS

EPS being “earnings per share”.

So while the supply chains of American and European manufacturers didn’t have the resilience of Japanese car makers, it saved a ton of money and made Wall St analysts and shareholders very happy.

But even Toyota supply chains had issues

The 9.0 earthquake in 2011 resulted in significant damage to Japan, and hurt their ability to build stuff.

Some supply chains, plastic resins, for example, recovered quickly.

Others, semiconductors, took months.

Even Toyota learned that not all supply chains are equal.

Supply chain disruption is inevitable

The structural design flaws in the Titanic were going to show themselves if it ever hit an iceberg. Which iceberg doesn’t matter.

The financial market asset bubble leading up to the 2008 global financial crisis was going to burst eventually. Which asset type was bid up to catastrophic heights doesn’t matter.

Not all inventory is excess

So Toyota started stockpiling semiconductor inventory, but not plastic resin inventory.

Because in their minds, semiconductor inventor was not “excess” as sooner or later they were guaranteed to need it.

And that is why during this global pandemic shortage of new cars, Toyota is the only car manufacturer on earth that continued to build cars when everyone else couldn’t.

Just-in-time vs resiliance

The tradeoff is real. As the example of Toyota and computer chips shows.

In modern supply chains, shortages are complex

And as disruption is inevitable, it needs to be planned for.

Short-term profits vs long-term gain

THIS is the cause of our supply chain disruptions and current shortages.

This is what leaves us vulnerable to supply chain shocks.

Our focus on boosting next quarter’s EPS (earnings per share) leaves us unprepared to handle inevitable disruptions in our supply chains.

We run as close as possible to the edge, on purpose, because Wall St wants us to.

And it works – until it doesn’t.