If you found this post via search, it probably makes sense to start with the first post in this series.

The prior posts in this series contain ideas that will help you understand more about how our economic vocabulary causes us to focus on things that matter very little while not paying any attention to things that matter a lot.

Table of Contents

Supply chains matter more than money flows

As I mentioned in the first post in this series, in conversations you hear about the economy or see online, people talk as if money is scarce, but if you have money there is no end of stuff you can buy with it.

That is exactly backward.

Currency issuing governments, central banks, and commercial banks could, if they wanted to (and fortunately they don’t want to), create an infinite amount of money.

But there isn’t an infinite amount of stuff to buy.

The pandemic shortages should be a teachable moment on this very idea.

But I don’t see any well-known pundits talking about this.

To paraphrase a slogan from the 1992 Presidential campaign of Bill Clinton, “It’s the supply chain stupid”.

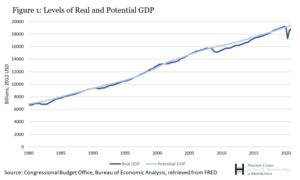

The wealth of a society is its productive output plus imports

While we measure wealth in dollars (or other currency units of choice) it really IS the total amount of goods and services available to the society.

The productive output seems obvious.

But why do I say “plus imports”?

Consider this:

If nation A and B go to war, and nation A wins, something that used to happen is nation A would impose some form of payment requirement on nation B.

You will send us X amount of wheat every year, or whatever.

Today, the US sends other countries dollars, which the US central banks create out of thin air, and the other countries send us cars, and consumer electronics, and mangos, and other real tangible stuff.

That stuff represents wealth, represents an increased standard of living.

Now, while all of the above is measured in dollars, we don’t eat dollars, we don’t live in dollars, and we don’t wear dollars.

For those dollars to be useful to us, we convert those dollars into the goods and services we actually want.

Having too little stuff is not good

Those are called shortages, shortages cause problems,. which we’re now experiencing.

Especially because people today seem to reject the idea that “shared sacrifice” is meaningful.

Thankfully at the time of WW2 people were open to the idea of shared sacrifice.

Today, not so much.

So when we don’t have enough of whatever, we suffer for it.

While having money matters, there MUST be stuff to buy

And that’s why I’m saying “It’s the supply chain, stupid”.

Unpaid and low paid “care work” matters

The obvious example here is for Mom and Dad to go to work. somebody has to watch the kids.

Someone has to watch the kids

The person who watches the kids is integral to Mom and Dad being able to work, being able to add to GDP, and having “economic value” per the standards of our society.

But “watching the kids” is considered low-value work.

It’s done either by someone who doesn’t work or people who get paid very little.

How do you get your dinner?

This is a fairly famous Adam Smith example:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest.

Smith, Adam. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of The Wealth of Nations. Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 1976. Book 1, Chapter 2, page 18

And he’s right. The butcher, the brewer, and the baker are not providing the stuff you need for your dinner out of any regard for you.

They’re earning money for themselves and their families.

But you know who cooked his dinner? And cleaned up after him? And kept house?

For almost his entire life?

His mother, Margaret Douglass.

And she DID do this out of benevolence.

And as she died only 6 years before he did, her nonfinancial support benefited him almost his entire life.

Unpaid care work enables paid work

But for some reason, her unpaid contribution to his financial success is rarely mentioned.

While everyone knows who Adam Smith is, this is likely the first time you ever saw his mother’s name.

Yet, without her unpaid care work, he would have had less time to think through his ideas and write his famous book, and quite literally change the world.

From the perspective of raising responsible kids, maybe it makes sense for one parent to stay home, focus on the kids, and guide their development.

But that doesn’t grow GDP.

What grows GDP is putting them in daycare and going to paid work.