If you found this post via search, it probably makes sense to start with the first post in this series.

It contains ideas that will help you understand more about how our economic vocabulary causes us to focus on things that matter very little while not paying any attention to things that matter a lot.

“Public sector” and “currency issuer”

We commonly use the phrases “public sector” and “private sector” when talking about the economy.

The public sector is the government and the private sector is not the government.

This is the wrong focus.

Currency issuer and currency user

What matters much more is “currency issuer” and “currency user”.

The currency issuer spends money into an economy which makes it available for currency users to use.

Why does THIS matter and not public sector vs private sector?

As issuers of a currency, currency issuers do not have to obtain currency in order to spend some.

Why? Because they are THE issuer of that currency.

Currency issuers are not like households and can NOT be like households.

Currency issuers do literally operate under a different set of rules.

They’re almost the opposite of currency user rules.

Currency users on the other hand can’t just conjure up currency from thin air (at least not legally) and for a currency user to spend some, they must first obtain some.

Public sector currency issuers

Includes Canada and the United States.

Public sector currency users

In Canada, this includes Ontario, Essex County, and the City of Windsor.

In the United States, this includes Arkansas, Miller County, and the City of Texarkana (AR).

The public sector currency users DO have to operate like households.

They MUST first obtain money in order to spend it.

If they run short, they have to borrow.

Only the currency user is different.

What the currency issuer spends on matters

In the prior post in this series, I discussed how what people do with the money the bank loaned them matters.

Some bank loans increase the production of goods and services.

Others create and fuel asset bubbles.

Something similar happens to money created by the central bank, by the currency issuer.

The velocity of money

Every dollar that gets spent into an economy gets spent multiple times.

Let’s pretend you work directly for the federal government who gives you a paycheck every two weeks.

Because they’re the federal government, when they pay you, they are literally spending money into the economy, as they do when they pay anyone.

You use that money for various purposes, but to not get too complex with this example, I’ll follow one chain of spending through the economy.

You buy groceries, and some of the money paid to you becomes income to the grocery store.

The grocery store in turn gives some of the money to an employee of theirs.

Who uses some of that money to buy a coffee at a local coffee shop.

Who uses some of it to pay one of their employees.

Who spends some buying gas.

Etc, etc, etc.

So, in a given time period, every dollar spent into the economy gets spent multiple times by virtue of the fact that the people to whom it is given then give it to others.

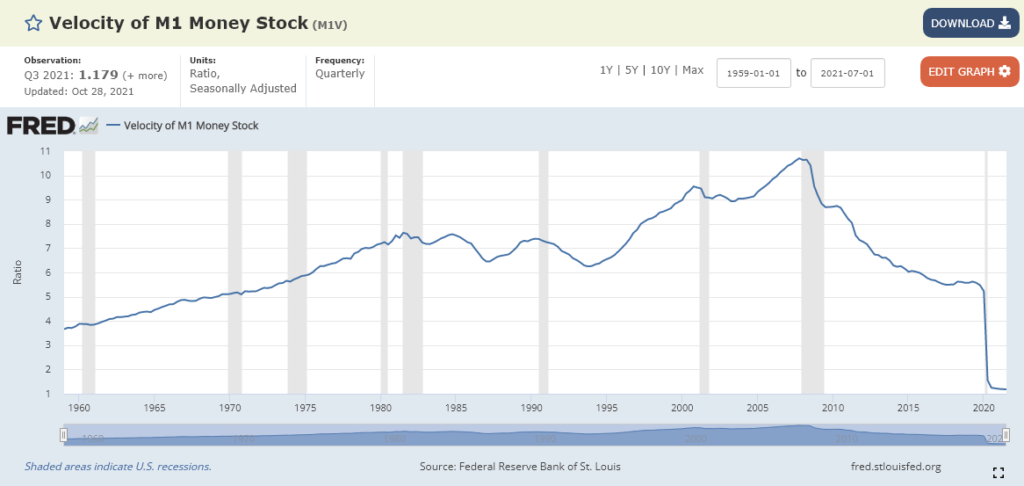

Now, let me show you something scary.

In my opinion, nothing shows the impact of Covid19 quite like the chart below.

I mean, damn! Talk about hitting the brakes.

Why does the velocity of money matter?

However, when we’re not in the midst of a global pandemic, we spend more.

And WHERE the currency issuer spends, and WHO they give the money to, determines how quickly, and to a certain extent how often, it gets spent again.

When the money goes to people who don’t spend it, it gets parked and is not used to stimulate economic activity.

When the money goes to people who do spend it, it gets spent and IS used to stimulate economic activity.

So, if economic growth is a high priority, currency-issuing governments should spend money with middle class and poor people who are more likely to spend it.

When the currency-issuing government spends with rich people, they fuel asset bubbles, as the rich people don’t need to spend it, so they use it to buy assets.