This is part of our series critiquing the book “What Has Government Done to Our Money?”. This post discusses the (I believe Libertarians’) belief that money creation should be done in a free market and governments creating money out of thin air is counterfeiting.

The “Rothbard” mentioned below is Murry Rothbard, the author of the book in question.

Page 32

Rothbard writes “”But if the government can find ways to engage in counterfeiting – the creation of new money out of thin air – it can quickly produce its own money without taking the trouble to sell services or mine gold”.

This ignores the anthropological evidence that money did not originate to make barter more efficient (the indirect exchange idea from earlier) and he ignores the anthropological evidence that money has always originated from the states need (or desire) to provision the military.

This topic is covered in the book “Debt: The First 5,000 Years” written by anthropologist David Graeber.

Page 39

Rothbard writes “… but they should have realized that a dangerous precedent had been set for government control of money”. This statement seems to fall back on the false premise that money came into existence to facilitate barter. The indirect exchange he describes earlier in the book.

It ignores the fact that anthropologists have determined that narrative to be false.

In the ancient world, the following seem to have always occurred together: armies, state controlled money, and taxation. In all of human history, in every even semi-complex society, per anthropologists, money has always been state controlled.

This is not a statement of what could be or what should be, but rather of what actually occurred, and occurs today.

Further down the page, Rothbard writes “For then debtors are permitted to pay back their debts in a much poorer money than they had borrowed, and creditors are swindled out of the money rightfully theirs”.

In economic practice, ancient societies where money originated had regular instances of debt forgiveness. The Bibilical jubilee is the best known example.

The rulers seemed to understand that excessive debt was a drain on the economy. When too many people were in debt bondage, the king couldn’t raise and provision an army.

So at various intervals, consumer debt was decreed to no longer exist. The idea was that people who make loans should assume some level of risk and be careful not to make loans to people who can’t pay.

The reward for this risk is the interest on the loan.

After WW1, the basic ideas of how economies were rewritten to start favoring creditors, and after WW2, that idea became further entrenched in our culture.

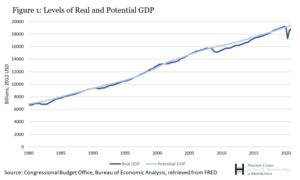

This idea that “debt bondage” is a drag on an economy is being seen today.

The 2008 financial crisis was triggered by excessive amounts of bad mortgage debt.

From the perspective of the creditors, this excessive mortgage debt was fine, as their risk was very low, because those mortgage debts were guaranteed by the US federal government.

Today, student loan debt is delaying the entrance of millions of millennials into the adult consumer economy, as their student loan payments are very high. Their ability to buy cars and houses is delayed years behind what their parents experienced.

The idea that creditors must be paid back at all costs and debtors who do not are confiscating creditor property is, in historical terms, new and seems to have been very damaging to economies around the world.

Beyond the 2008 mortgage crisis and the current student loan debt load hampering the entry of millennials into the adult consumer economy, what some call debt bondage are constricting the economies of Greece, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela.

Page 42

Rothbard writes “Invariably, private banks are prohibited from issuing notes, and the privilege is reserved to the Central Bank. The private banks can only grant deposits. If their customers ever wish to shift from deposits to notes, therefore, the banks must go to the Central Bank to get them”.

This may be a case of me not understanding what they mean by “notes”, but if notes mean currency backed by gold and/or silver where there is not enough gold and/or silver to redeem all the notes, the issuing of notes by regional banks occurred in the US prior to a national bank even existing (which occurred in 1863).

So the issuing of these notes was not dependent upon a government bank issuing currency.

Today, banks get their money from the Central Banks, and banks issue notes in the form of loans.

If I’m understanding correctly, Rothbard is saying that between 1913 (when the Central Bank was created), and some date between 1913 and today, that banks that were not the central bank did not issue “notes” or currency in excess of the gold or silver on deposit.

If so, does anyone know where can I learn more about this?