When World War 2 came to an end, the Federal Reserve had a dual mandate to 1) keep the interest rates on government securities low as desired by the Treasury which paid that interest rate, and 2) target a low inflation rate.

This was a bank regulation that created a dual mandate problem.

The dual mandate problem

The problem was those two mandates had opposing prescriptions. To keep interest rates low it was necessary that demand for Treasury securities not outstrip the supply of Treasury securities, thereby causing an increase in the cost of these securities (the interest rate), but these very same Treasury securities were used to increase and/or decrease banking reserves, which affected the availability of private credit, which influenced the level of inflation.

————————————

This post is part of a larger series and sub-series.

Here is a link to the series: The history of banks and banking regulation

and to the sub-series: United States Banking and Bank Regulation History

————————————

At first glance, it might seem that increasing the supply of Treasury securities would remove reserves from the banking system as it does today, so why didn’t that one prescription target both mandates?

Because the Federal Reserve can buy and hold Treasuries, thereby providing funds to the US government, while simultaneously not selling treasuries to or buying from the primary dealers, which is what affects the level of banking reserves.

In summary, it’s complicated. Perhaps excessively so. Perhaps intentionally so.

The Fed policy during, and after WW2 was a cap on Treasury interest rates. 2.5% on long-term bonds and 0.375% on 90-day bonds, and this price was maintained for both the Treasury and the primary dealers.

And while this was good for the Treasury, as it kept their interest payments on those bonds low, the Fed can’t force the primary dealers to buy and sell bonds, so managing levels of banking reserves requires more flexible pricing.

This led the Fed to feel stuck in its ability to influence the amount of private credit available, which is one of their primary mandates. They were then, and still are, operating from the belief that the amount of money (and bank loans are money) in the economy is the primary driver of inflation and deflation.

The separation of interest rates and banking reserves

It took a lot of discussions and even a Federal Reserve Board of Governors meeting with President Truman at the White House to reach an agreement on this. The Treasury agreed that its desire for it to have a low-interest rate on government securities was hampering the Feds ability to manage bank reserves.

Having said that, there wasn’t even agreement by people present at the meeting what had been agreed to. Truman issued a statement that the FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) “pledged its support to President Truman to maintain the stability of Government securities as long as the emergency lasts”. The Fed chairman, Marriner Eccles (pictured above), issued a somewhat different statement.

However, the Fed informed the Treasury that effective February 19, 1951, the Fed would no longer “maintain the existing situation”. The official statement was that the Fed would continue to support the price of five-year treasury securities for a short time, but after that, bond pricing would be based on increasing supply and demand to target banking reserve levels.

A joint Fed and Treasury statement was issued on March 4th, 1951 stating that they had “reached full accord with respect to debt management and monetary policies to be pursued in furthering their common purpose and to assure the successful financing of the government’s requirements and, at the same time, to minimize monetization of the public debt”.

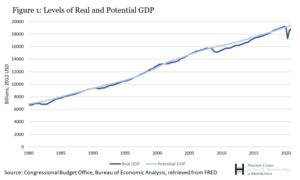

This market in US government securities where the price is strictly a function of supply and demand continues to this day. At least until March of 2020 when the reserve requirement was reduced to 0% to assist with the financial impact of the Covid pandemic. But this is not expected to be permanent, so for the sake of the larger picture, let’s ignore this for now.

When the Fed wants lower interest rates, it increases bank reserves to make credit more plentiful, and when the Fed wants higher interest rates it drains reserves from the bank systems. So managing to an interest rate became an exercise in managing the level of reserves in the banking system which was accomplished by selling and buying treasury securities to and from the primary dealers.