This post is part of a series of posts that summarizes the book Angrynomics by Eric Lonergan and Mark Blyth.

If you found this post via search, it probably makes sense to start with the link to the full series, which is both here, and above.

Table of Contents

Can dual interest rates be part of the solution to angrynomics?

I confess, it is taking me a while to wrap my head around the idea of dual interest rates, and I’m not sure I fully get it yet, so this post may change later as I learn more.

From the book:

Dual interest rates would allow central banks to separately target the rate of interest savers receive on their deposits and the rate borrowers pay on their loans.

Lonergan, E., & Blyth, M. (2020). Angrynomics. Agenda Publishing. Page 149.

But don’t we do that already? Aren’t depositors paid one interest rate (a lower one) and borrowers charged another (a higher one)?

The answer to the above question, as best I can ascertain, is that commercial banks already have a dual interest rate policy, but most central banks do not.

And furthermore, what the authors are recommending is to flip the commercial bank model on its head, where the central bank pay a small interest rate on deposits (say 0.25% or 0.5%), which I should add most central banks pay zero percent today, and charges a LOWER interest rate on loans.

But…. how does a central bank charge a lower interest rate than 0.25%? By paying 0%?

By charging negative interest rates.

Negative interest rates?

What does that even mean?

Let’s look at negative interest rates from two perspectives.

What are negative interest rates when “paid” to depositors?

If a bank “pays” negative interest rates to depositors, it means the depositors are paying the bank for holding their money. You can think of this as “storage fees” if you like, as they look very similar.

If you were to deposit $1,000 into a central bank that “paid” a negative interest rate of 0.5%, at the end of one year you would have paid the bank $5 to hold your deposit and you would have $995.

No one who wants to make money would do this. They would find some other place to put that money, which it turns out is the point.

The purpose of central banks paying negative interest rates on deposits is to discourage the “parking” of money where it’s not doing much good and to encourage “productive” investment, which I’ll expand on later.

What are negative interest rates when “charged” to borrowers?

If a bank “charges” negative interest rates to borrowers, it means the borrowers get “extra money” every time they take out a loan. You can think of this as “free money” if you like, as they look very similar.

If you were to borrow $1,000 from a central bank that “charged” a negative interest rate of 1.0%, at the end of the year they will pay you an extra $10.

If you’re looking to make money, this looks like a pretty good deal.

The purpose of central banks charging negative interest rates on loans is to encourage the borrowing of money for investment.

The goal is not borrowing per se, but rather investment spending.

Why wouldn’t investors then just “play the spread”?

I’ll get back to the main point in a minute, but this little segue keeps knocking me upside the head from the inside.

If a central bank will pay me 1.0% to borrow money and charge me 0.25% to deposit money, why wouldn’t I simply borrow a bunch, deposit it, and keep the spread?

My answer is: I don’t know, and as the authors are both much more experienced in finance and money dynamics than I am, this is what leads me to believe I’m missing something important here.

The purpose of dual interest rates

Supported by, if needed, negative interest rates is to discourage money being “parked on the sidelines” and to encourage “investment spending”.

The idea here seems to be that money does more good when it’s spent, because it’s the spending that stimulates economic growth.

Productive investment vs speculative investment

I said earlier I would get back to this, and it’s time.

Investment is spending money to make money.

And there are two ways to do this.

Investors can spend money which increases the production of goods and services and make money because the business venture is profitable.

Investors can also spend money on assets (stocks, bonds, real estate, hedge funds, etc) with the expectation that the assets will increase in value over time.

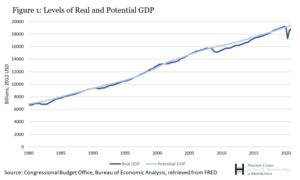

These two forms of investment have very different economic outcomes.

Investing which increases the production of goods and services grows the economy, as the true wealth of a nation is the aggregate production of goods and services. While we measure wealth in money, wealth is actually what is available to be bought, not the money used to do the buying.

Investing in assets fuels asset bubbles, which on occasion get bid up to astronomically ridiculous valuations. This becomes a huge problem when these asset bubbles burst and it turns out everyone took out debt to fuel their asset purchases and the inability to repay that debt ripples through an economy’s financial systems and grinds the whole thing to a halt.

This is in fact what happened in 1929 when debt was used to buy stocks on margin, and in 2008 when the entire crisis was created around providing mortgages, en masse, to people who had no ability to make their mortgage payments.

Asset bubbles can be great if you time it well and buy low and sell high, but they can crater entire economies when they’re built on debt which, when the asset value craters, can suddenly not be refinanced.

It turns out, Eric has published posts on this very topic

Which I link to below for your reading enjoyment.

He wrote and published this one on his blog: Dual interest rates always work.

He co-wrote and published this one on the blog of VoxEU: Dual interest rates give central banks limitless fire power