The rational expectations theory of inflation is part of the neoclassical focus of modern economics (the word “rational” probably gave it away), which was first described in a paper by John F. Muth published in 1961.

I think there is evidence to suggest that it is both very influential, and used to justify poor economics, which ironically is why we need to pay attention to it.

It became popular in the 1970s as our switch to neoliberal capitalism occurred.

Neoliberal capitalism has been built upon neoclassical economic ideas.

If you found this blog post via search, it probably makes sense to start at the first post in this series (the link is above), as it contains information and ideas that are relevant here.

Table of Contents

What is the rational expectations theory?

The basic ideas of the rational expectations theory are similar to the basic ideas of neoclassical economics in general.

That people make economic decisions based on three primary things:

- Rationality

- What they know or believe to be true

- Past experiences

And never mind that the Nobel Prize in Economic Science was awarded to Richard Thaler in 2017 precisely for demonstrating that most economic decisions are NOT made rationally.

For purposes of using theory as the basis for public policy, that needs to be put aside.

Essentially, the idea, as I understand it, is that past outcomes influence current decisions, which of course influence future outcomes.

This is as true of future price levels as it is of other aspects of economics.

There is a further belief that because we make rational decisions, based on what we know and our past experiences, that most of the time we make good decisions.

Which presumably leads to good aggregate economic outcomes.

What evidence supports this idea

Not all outcomes are good

I believe there is evidence that past experiences create expectations.

I’m not sure I agree that this leads to good decisions or good economic outcomes.

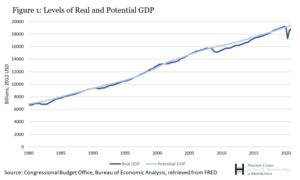

For example… After the 2008 global financial crisis, central banks started pumping enormous amounts of money into banking systems, which resulted in (among other things), interest rates staying low, and asset prices staying high.

Interest rates stayed low because the central banks injected money into banking systems partially to meet their mandate of hitting a target interest rate, and by providing this seed money (or reserves as they’re properly called) they created a sufficient supply of credit such that the cost of credit (interest rates) did not rise.

Asset prices stayed high because much of the newly created money (both money created by the central banks and subsequently money created by the commercial banks) was used to buy assets: stocks, bonds, real estate, etc.

This money supported demand for assets which not only kept asset prices high, but caused asset prices to rise.

This created an expectation that interest rates would stay low, and that central banks’ money creation would prop up economies, or at least the asset markets within those economies.

Which, if you’re an investor getting rich on asset appreciation, is a good outcome.

Examples which seem to support the idea

Thomas J. Sargent, who wrote the book in the image at the top of this post, published an article containing a few examples.

All of which seem valid and reasonable.

The price of an agricultural commodity, for example, depends on how many acres farmers plant, which in turn depends on the price farmers expect to realize when they harvest and sell their crops.

…the value of a currency and its rate of depreciation depend partly on what people expect that rate of depreciation to be. That is because people rush to desert a currency that they expect to lose value, thereby contributing to its loss in value.

…the price of a stock or bond depends partly on what prospective buyers and sellers believe it will be in the future.

My conclusion

The evidence supports the idea that expectations of future prices do in fact affect future price levels, but there are situations where this can lead to very poor economic outcomes for most people.

While this doesn’t make this theory wrong, it does, in my opinion, make this theory a bad basis for public policy.