If you found this post via search, it probably makes sense to start with the first post in this series.

The prior posts in this series contain ideas that will help you understand more about how our economic vocabulary causes us to focus on things that matter very little while not paying any attention to things that matter a lot.

Table of Contents

What causes inflation?

To me, this is one of the most interesting parts of how our economic vocabulary steers us wrong.

Would you believe that we don’t really know what causes inflation?

That is to say that while people have competing ideas about what causes inflation, there are situations to dispute them all, and there is no General Theory of Inflation as you may have thought.

Some of the competing theories are listed below, and I may have left some out I haven’t yet stumbled across.

- Monetarist Theory of Inflation

- Market-Power Theory

- Demand-Pull Theory

- Cost-Push Theory

- Structural Theory

- Rational Expectations Theory

Monetarist Theory of Inflation

This is probably the most well-known, and it simply states that adding money to the economy causes inflation.

It is based on a very famous equation, that has two parts.

I apologize in advance but this part of the post includes a little math.

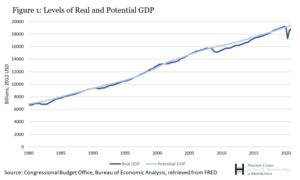

One way to describe GDP is it’s all the money in the economy times the number of times each dollar changes hands.

GDP = MV, where M = money in the economy, and V = velocity of money, or how often each dollar changes hands.

GDP is also the total sales in an economy.

GDP = PT where P = the prices paid and T = transactions where money changed hands.

So, if GDP = MV and GDP = PT, then MV = PT.

For the record, this is not a controversial statement and I doubt you’ll find any economists anywhere who disagree with this equation.

A simple rearrangement of that equation shows that P = (MV) ÷ T.

This also is not a controversial way to look at things. It’s a simple rearrangement of the equation.

This clearly shows that when V (velocity) and T (transactions) are stable, any increase to M (money) causes an increase to P (prices).

Pretty straightforward, right?

So how do we know the quantity of money theory of inflation is wrong?

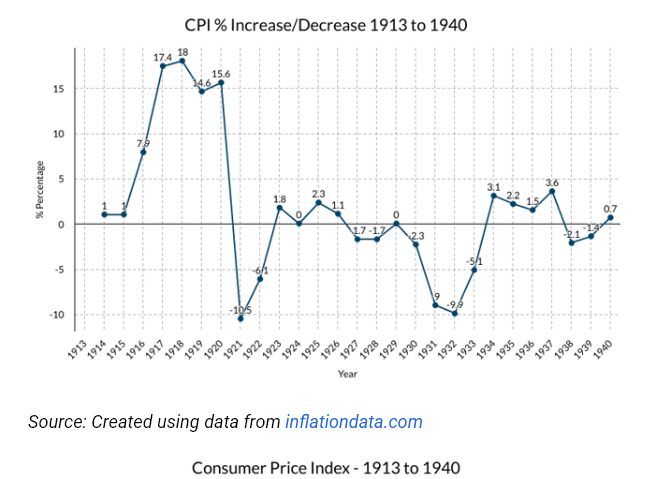

Because after the 2008 great financial crisis, central banks all over the world pumped MASSIVE amounts of money into their economies for a period of years, with no inflation.

This also occurred when money was pumped into the economy during the great depression started in 1929.

Inflation was high during WW1, fell to negative and stayed low during the roaring twenties, went negative a bit as the depression was starting, and stayed low until WW2.

This tells us that after the asset bubbles burst in 1929 and 2008 and triggered economic calamities, V and T were not stable.

Market-Power Theory

The basic idea here is firms with monopoly or near-monopoly power, set their prices and we are happy to pay because, well, we just are. Or they have monopolies and we have no choice.

Something like that.

And if some of the firms with near-monopoly sell things that are inputs to a wide range of products, then the price of everything goes up, which is inflation.

If for example, the price of oil was to artificially be raised due to monopoly power, it would ripple through the entire economy due to our deep and wide addiction to oil

Demand-Pull Theory

This one is really simple to understand, and while it’s likely not the sole cause of inflation, due to the “obviousness” of the statement, it has some effect.

When demand exceeds supply, prices go up.

And when the thing whose price goes up is fundamental to our economy, like the price of oil, or the price of freight transport, the price of a lot of stuff goes up, and we call that inflation.

Due to the obviousness of it, it has to be at least partially true.

Cost-Push Theory

Like the demand-pull theory, this one too is obvious, and as a result, has to be at least partially true.

It basically says when the cost of production inputs go up, inputs such as the cost of wages and/or the cost of raw materials, the stuff produced with that labour and with the raw material also goes up.

Labour of course is a common input to everything, and some materials (again, oil is a good example) are as well.

Structural Theory

This one is a bit more complex and subtle.

It also relates to developing economies.

The basic idea is some economies have structural issues that prevent things from working “right”.

That the usual deterrents to inflation, adequate supply of investment capital, adequate supply of goods, adequate but not overwhelming demand, are sometimes not enough to keep inflation in check.

They argue the primary determinants of inflation are:

- Inelastic supply of agriculture output requires periodic and sometimes sizeable food imports.

- Government budget restraints of previously supported (subsidized) industries.

- Hampered flow of capital goods into the country, for various reasons.

I don’t pretend to fully understand this one and I list it for sake of the list being more complete.

Rational Expectations Theory

The basic idea here is that our expectations of what will happen influence what does happen.

There is continual feedback from past outcomes to influence current expectations, which causes us to adjust our forecasts for the future, which sometimes creates “tolerance” of price increases, which in fact creates price increases.