First, let’s compare common definitions of what inflation is.

Table of Contents

Definitions

Investopedia

Inflation is the decline of purchasing power of a given currency over time.

Fernando, Jason. “Inflation.” Investopedia, 17 June 2021, www.investopedia.com/terms/i/inflation.asp.

Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

How do you measure inflation? Statistical agencies start by collecting the prices of a very large number of goods and services. In the case of households, they create a “basket” of goods and services that reflects the items consumed by households. The basket does not contain every good or service, but the basket is meant to be a good representation of both the types of items and the quantities of items households typically consume.

“What Is Inflation?” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, 21 Oct. 2014, www.clevelandfed.org/en/our-research/center-for-inflation-research/inflation-101/what-is-inflation-get-technical.aspx.

Forbes

Inflation occurs when prices rise, decreasing the purchasing power of your dollars.

Schmidt, John. “How Inflation Erodes The Value Of Your Money.” Forbes, 3 May 2021, www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/what-is-inflation.

International Monetary Fund

Inflation measures how much more expensive a set of goods and services has become over a certain period, usually a year

Oner, Deyda. “Inflation: Prices on the Rise.” International Monetary Fund, 1 June 2018, www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/basics/30-inflation.htm.

European Central Bank

In a market economy, prices for goods and services can always change. Some prices rise; some prices fall. Inflation occurs if there is a broad increase in the prices of goods and services, not just of individual items; it means, you can buy less for €1 today than you could yesterday. In other words, inflation reduces the value of the currency over time.

“What Is Inflation?” European Central Bank, 2021, www.ecb.europa.eu/ecb/educational/hicp/html/index.en.html.

Vox

Inflation refers to a general rise in the level of prices.

Yglesias, Matthew. “Inflation, Explained.” Vox, 11 May 2015, www.vox.com/2014/7/24/18080392/inflation-definition-and-explanation.

So, a GENERAL rise in prices?

That seems to be the common thread.

If costs in one sector of the economy go up, it may or may not create inflation depending upon how broadly that sector affects others.

When the cost of figs goes up, it’s not inflation.

When the cost of fertilizer goes up, it might be.

When the cost of oil goes up, it definitely is.

Can inflation be good?

Yes, and off the top of my head, I can think of two different ways.

For individuals: Paying off long term debt

Let’s say you’re buying a house, either to live in or as an investment property that you plan to hold for a long long time.

When you take out a 30-year mortgage, your initial payments are always in “today’s” dollars.

10, 15, 20 years down the road, you’re paying the mortgage payment in “yesterday’s” dollars.

Because the monthly mortgage payment stays the same, but the purchasing power of the money decreases, you’re making your payments with less valuable (cheaper) money.

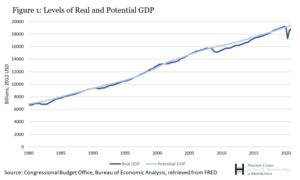

For the economy: It’s about growth

How does inflation encourage economic growth?

By causing us to NOT put off big-ticket purchases in order to save money later.

Let’s say you’re planning to buy new kitchen appliances or a new car.

If the central bank planners are successful in hitting their 2% per year inflation target, every year that purchase is going to cost you 2% more.

If you wait 5 years, it will cost you 10% more (10.4% more actually due to the 2% being compounded every year).

So inflation encourages us to NOT defer big-ticket purchases, and when we make these purchases sooner we add to GDP sooner.

Is there more?

Sort of.

The more is not inflation per se, but rather is about price increases, which may, or may not, be inflation.

Price increases: Can they be good?

From here on in this post, I’m changing the question from “can inflation be good?” to “can price increases be good?”.

By doing so, I’m attempting to consider morality in the context of the idea that all price increases are bad.

Please consider that every time one person pays more for something, someone else receives more.

Relative to the price increase being good or bad, doesn’t it matter who is receiving more, and why?

For who?

It’s rare for people to ask this question, and in my case when an economics professor (John T. Harvey Ph.D. of Texas Christian University) asked this question in an interview, it stopped me.

He used two examples:

Example #1: When you go to McDonald’s and your $5.00 hamburger now costs $5.50, and as a result of that, the people working there now make $15.00 an hour vs $7.25, is that good?

I say yes. I would gladly pay the $5.50 if I ate hamburgers.

Example #2: When the insulin you need to stay alive increases in price from $200 a month to $600 a month, and as a result of that, the pharma company that makes it now pays out $2B in dividends every quarter, is that good?

If you’re a shareholder receiving a dividend payment, it’s good.

If you’re a diabetic trying to afford life-saving insulin, it’s terrible.

So, it depends?

Exactly.

In order to answer the question of whether prices increases are good, bad, or neither, we must first look at the bigger picture and ask, for who?

If you feel the people receiving more money SHOULD receive more money, to you, those price increases are good.