Feminist economics is not exclusively about gender issues and inequality.

It seems that at its core it analyzes how and why unpaid care work is not considered to be economically valuable when unpaid care work directly enables the activities we do think are economically valuable.

Researchers in feminist economics draw some ideas from neoclassical economists, institutional economists, and Marxists.

It started in the late 1980s early 1990s by several people, and it seems the 1998 book “If Women Counted” by Marilyn Waring is considered by some to be the founding document.

This post is a summary of chapter 9 (Feminist economics) of the book Contending Perspective in Economics by John T Harvey Ph.D. I’m summarizing this book because it’s such a great little book (151 pages, but packed full of insights).

Table of Contents

What does it mean to practice economics?

This is a fundamental question other schools of economic thought seem to feel everyone already knows.

But to feminist economists, the more “standard” answer, which is economics is about objective facts and value-free analysis, is discarded.

They believe the practice of economics requires subjective interpretations of what we observe and recommendations for changes that will make people’s lives better.

And that all theories and models are of necessity built on ideological and philosophical assumptions that we are often unaware of.

When you think about it, their idea that the purpose of economics is to make things better and that “better” is a subjective idea, their focus on this seems reasonable.

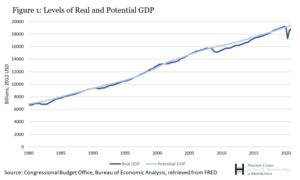

They even go so far as to question whether GDP is a meaningful measurement.

If GDP is an important measurement of the value of our contributions to society, then a stay-at-home parent provides less value to society than a parent who pays for childcare, to enable them to go to a paying job, even if that job pays so little it just covers the cost of childcare.

Even Adm Smith fell into this trap.

In his famous example of “How do you get your dinner?” he showed how specialization of tasks, and individuals being concerned about their own self-interests, results in increased trade and a rise of our collective material wealth.

Yet he didn’t give two thoughts to who cooked his dinner.

Spoiler alert: It was unpaid care labour. His mother cooked his dinner.

Somehow the contribution his mother provided to his dinner being ready was just taken for granted, even though it was integral to him having dinner.

But this questioning of “what has value?” goes beyond gender.

The visible differences by which we identify who is a member of which race matter in our society, yet race is a social construct, not biological differences.

What we today call “race” was created in the 17th century to justify the African slave trade.

So, from a biological sense, your race does not matter, but from a social and economic sense, it matter a lot.

To feminist economic researchers, these are not minor oversights.

These are the ideological and philosophical beliefs and values upon which we build our economies and our societies.

If unpaid care work has no economic value, then from a public policy perspective, it’s a low priority.

And if only market-based activities have economic values, then most of what people did through the entire course of human history had no economic value.

Our focus on markets vs non-markets is not divine law, it’s ideological and cultural.

No matter how many neoclassical economists argue otherwise.

So, what is “feminist economics”?

Feminist economics is, therfore, an approach that asks us to consider the impact of culture not simply on the economy, but on economics.

Harvey, J. (2016). Contending Perspectives in Economics: A Guide to Contemporary Schools of Thought (Reprint ed.). Edward Elgar Pub. p. 136

Influences of other schools of thought

The other economic schools of thought influencing feminist economics are neoclassical economics, Marxism, and institutionalism.

Clearly, some of their ideas were carried over while others were rejected, but as a result of this, feminist economics may be the most pluralistic school of economic thought.

Neoclassical influences

It seems the influence of core ideas is the main theme here.

Feminist economic researchers reject the ideas that economic agents are rational and that markets always produce the best outcomes.

They argue those ideas come from the same male biases that cause us to not value unpaid care work.

They argue that the neoclassical economic idea that agents in a system end up in “economically optimum” roles ignores the fact that historically, in our culture, that has been true for white men more so than for anyone else.

Feminist economists argue the standard neoclassical models do not explain why home care and child care have almost exclusively been the domain of women.

Most feminist economists do however accept some neoclassical economic ideas, such as formal and informal markets, maximizing behavior, stable preferences, and equilibrium.

Marxist influences

It seems the principle Marxist ideas they reject, are the idea of exploitation based on wage labour, and the idea of economic surplus being kept by the capitalist and not shared with the workers.

Not because they’re not true, but because they fall into the same trap of not acknowledging the value of unpaid care work.

While these basic Marxist ideas is not seen as wrong, they’re seen as woefully inadequate to explain why women perform most of the unpaid care work.

Having said that, many feminist economists are drawn to some of Marx’s social theories of oppression, power dynamics, and alienation.

Their idea seems to be that while Marxist ideas have been traditionally based on class and market transactions, some of his core ideas have merit and can be used to describe non-market phenomena.

Institutional influences

The union between feminist economics and institutional economics seems to be more harmonious than the other two.

Both acknowledge that the influence of culture and ideology is so strong that many don’t even see it.

It’s like that question of whether fish are aware of water.

If it’s all around you, do you lose awareness of it?

The institutionalist idea of “ceremonial values”, the “past-binding” behaviors that exist within all cultures, explains how women wound up doing the bulk of unpaid care work.

This happened not from logic, or market forces, or rational thought.

It happened because men ran things and “this is how we do it”.

The feminist economists agree with the institutionalist that:

The inferiority of women in our society, they argue, has its roots in our shared cultural beliefes that have been passed from generation to generation and, under most circumstances, accepted without question – even by women.

Harvey, J. (2016). Contending Perspectives in Economics: A Guide to Contemporary Schools of Thought (Reprint ed.). Edward Elgar Pub. p. 142

From both the institutionalist and feminist economics perspective, sexism is a ceremonial value.

Methods

First and foremost is the belief that economics is not, and can not be, free of value judgments. That is not a thing.

That the inferior status of women is taken for granted by most people without even thinking about it is not limited to economics, but reflects our wider cultural values.

They’re big on pluralism, which is consistent with their broader philosophy of how beliefs and values shape economic thinking.

Views of human nature and justice

They believe that home sapiens are social animals who are heavily influenced by cultural values.

In terms of justice, feminist economists argue that all people, independent of race, or gender, or sexual orientation, should be free to make their own choices and that the social and legal obstacles to this should be removed.

As a result of their broader view of how things work, feminist economic policy recommendations necessarily transcend mere fiscal and monetary policy.

Criticisms

Economists from other schools of thought argue that while the ideas of feminist economics have merit, are important, they’re not economics, they’re sociology.

Also, some other economists think that economic schools of thought that de-emphasize mathematical analysis lack the rigor of real science.