New institutionalism is the economic offspring of neoclassical economics and constitutionalism.

New institutionalists believe the quasi rational choices individuals within a market-based economy make are limited and guided by the societal institutions of that society.

Like other economic schools of thought, new institutionalism was started when an economist wrote an article or two that didn’t fit well within an established school of economic thought.

In this case, it was two articles written by Rondal Coase, one in 1937 and the other in 1960. He proposed that our cultural/societal institutions guide/limit important economic ideas and behaviors such as property rights and transaction costs.

The idea of transaction costs is a big deal to new institutionalists. and are seen as a reason institutions exist.

And that in order to understand why things are the way they are, you must understand society’s institutions.

The term “new institutional economics” was coined by Oliver Williamson in 1975.

This post is a summary of chapter 8 ( New Institutionalism) of the book Contending Perspective in Economics by John T Harvey Ph.D. I’m summarizing this book because it’s such a great little book (151 pages, but packed full of insights).

Table of Contents

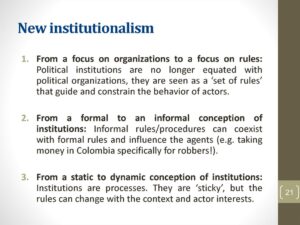

Institutions vs organizations

As with institutionalism, these are key concepts and the difference between them is really important.

Institutions

Institutions are rules.

They can be formal and written down. Think about constitutions, criminal codes, building codes, etc.

Or they can be informal and are things everyone just knows. Wipe your feet before entering a home, wear a tie, shave your legs, go to church, care about football, and don’t disrespect your parents, especially if you’re one of my children.

Organizations

Organizations follow institutional rules.

Banking is an institution. Wells Fargo Bank is an organization.

Football and football fandom is an institution. The Dallas Cowboys is an organization.

Politics is an institution. Political parties are organizations.

Are you a good institution or a bad institution?

Yes, there are bad institutions. And there are institutions that contain elements of both.

Banking

If banking wasn’t an institution, and if couldn’t simply deposit your receipts into a bank account and on occasion get bridge loans from the bank, your life would be much more difficult.

You could only accept cash, you would need a safe to keep it in, when you needed to buy something you would have to take wads of cash with you, etc.

However, the 2008 great financial crisis was caused by banking.

Those bankers packaged mortgages that the borrowers could not make the payments on into mortgage-backed securities and sold them to investors as AAA investments when they knew they were total crap and their values would plummet once the bubble burst.

So… is banking a good institution or a bad institution?

Crime

Let’s say for example own a small business on Main St. A dry cleaner.

Let’s further pretend that in your town there are organized crime folks who shake down local businesses for protection money, and you, like everyone else on Main St pay because rebuilding after being burnt down would be more expensive than paying the protection money.

Not a good institution, definitely.

Politics

It sometimes happens that the people who have the power to “fix” institutions are the very ones who benefit from them being “broken”.

Think of modern American crony capitalism.

Only Congress can make money in politics illegal at the federal level, but until we collectively vote out anyone who takes corporate money, they have no incentive to.

So systemic inequality lingers in our institutions because it’s working for those who make the rules.

Examples of economic analysis

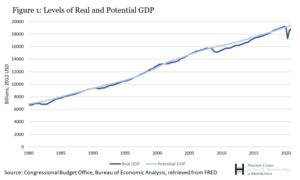

Dutch banking collapse of 1763

There was a war (1756 to 1763).

Bankers in Amsterdam did a brisk business financing governments and war merchants (what we now call defense contractors).

Due to the war, there were shortages that led to rising prices.

The higher prices resulted in higher profits which made it easier to pay back loans.

Since banks make money on loans, and businesses are having no trouble making their payments, they make more and more loans to more and more people.

Because of the interlocking nature of firms selling to and (through the banking system) borrowing from each other (back then banks didn’t just create money from thin air to fund a loan), to keep the money flowing it was necessary for everyone to make their payments.

Which they were doing.

But if one firm was to miss payments, the person they didn’t pay would have trouble making theirs, but that was not a problem.

Then in 1763, the war came to an end.

Which was great for the soldiers.

Shortly afterward, a fairly small account at a fairly small bank couldn’t sell their goods for a suitable price and couldn’t make their loan payments.

This caused that bank to be a bit short of cash, and they missed payments to their creditors.

This caused their creditors to be a bit short of cash.

This quickly rippled through the economy and suddenly all the war merchants and banks in that system had loans they could not pay.

It led to the economic collapse of those businesses and catastrophe for their economy.

American banking collapse of 2008

A boom in housing prices leads to a bit of a land grab to buy houses as investments.

Which leads to demand for mortgages.

Which leads to a boom in mortgage lending.

These mortgages got bundled into Mortgage Backed Securities which could be traded like stocks and bonds, and the returns on these were good.

Institutional investors wanted more.

Even after the banks funding mortgages ran out of borrowers who had the means to make their payments.

But, profits are profits, and if the investors wanted mortgage-backed securities, the banks simply had to provide mortgages to people who didn’t have the means to make their payments.

What the heck, they had no plans to hold the mortgages for 30 years and collect the payments anyway.

They were selling them in the secondary mortgage markets a day or two after they closed.

Thereby making collecting on them somebody else’s problem.

Heck, investment banks even created insurance-like products to guarantee that if the value of mortgage-backed securities did fail, the “credit default swaps” as they were called, would pay.

The problem is the banks sold far more credit defaults swaps than they could ever make good on, and since those insurance-like products were not in fact insurance, they were not regulated like insurance and no one bothered to ask if the firms selling them could make good on them if they had to.

But no problem, everyone was making their payments, so selling credit defaults swaps brought in some sweet profits.

Then, the mortgage holders who couldn’t make their payments stopped making their payments, em masse.

And the banks holding those mortgages found themselves short on cash.

And the banks who sold all those credit default swaps didn’t have the means to make good on them.

This inability to pay rippled through not only the US banking system but the global banking system, plunging us all into the great recession.

Analysis

In both cases above, the initial firms that failed did not appear to carry any more risk than anyone else, they were just the first to experience the cash shortfall.

An institutionalist analysis of this deals not only with the causality of these failures of capitalism but how the rules of banking allowed them to occur in the first place.

Our markets are a reflection of the morals of the people making the rules for the markets, when the rules allow large-scale fraud, which can be very profitable, large-scale fraud happens.

By contrast, the Canadian banking system did not fail in 2008, or 1930, or 1907).

Why? Because the rules of Canadian banking are different.

In Canada banking is boring, banking is stable, banking is strictly regulated to not allow for business models based on fraud.

Method

As with neoclassical economists, individuals are still the focus of analysis of economic activity, behavior, and phenomena.

New institutionalists focus on individuals, scarcity, and choice,.

But unlike neoclassical economists, they believe institutions matter, as do societal power structures, culture, ideology, and history.

New institutionalists, like institutionalists, examine institutional structures, how they came to be, and what the societies they operate in are like.

But unlike institutionalists, they see individuals as pseudo-rational, as the focus of change, and as the basic unit of economic analysis.

Views of human nature and justice

Individuals are the true agents of change in society, but their choices are guided and limited by institutions.

Individuals create institutions.

These institutions either increase (crime, crony capitalism) or decrease (commercial banking) transaction costs for the individuals.

People are guided by self-interest, and quasi-rational, but never really have sufficient information to make fully rational decisions.

New institutionalists, like Austrian economists, believe justice is outcomes that show the collective preferences of the society.

Criticisms

As with institutionalists, economists in other schools of thought claim new institutionalism is not really economics, but rather historians and sociologists.

Institutionalists also criticize new institutionalists for not accepting the idea that institutions exist simply because homo sapiens are social creatures, and for no other reason.